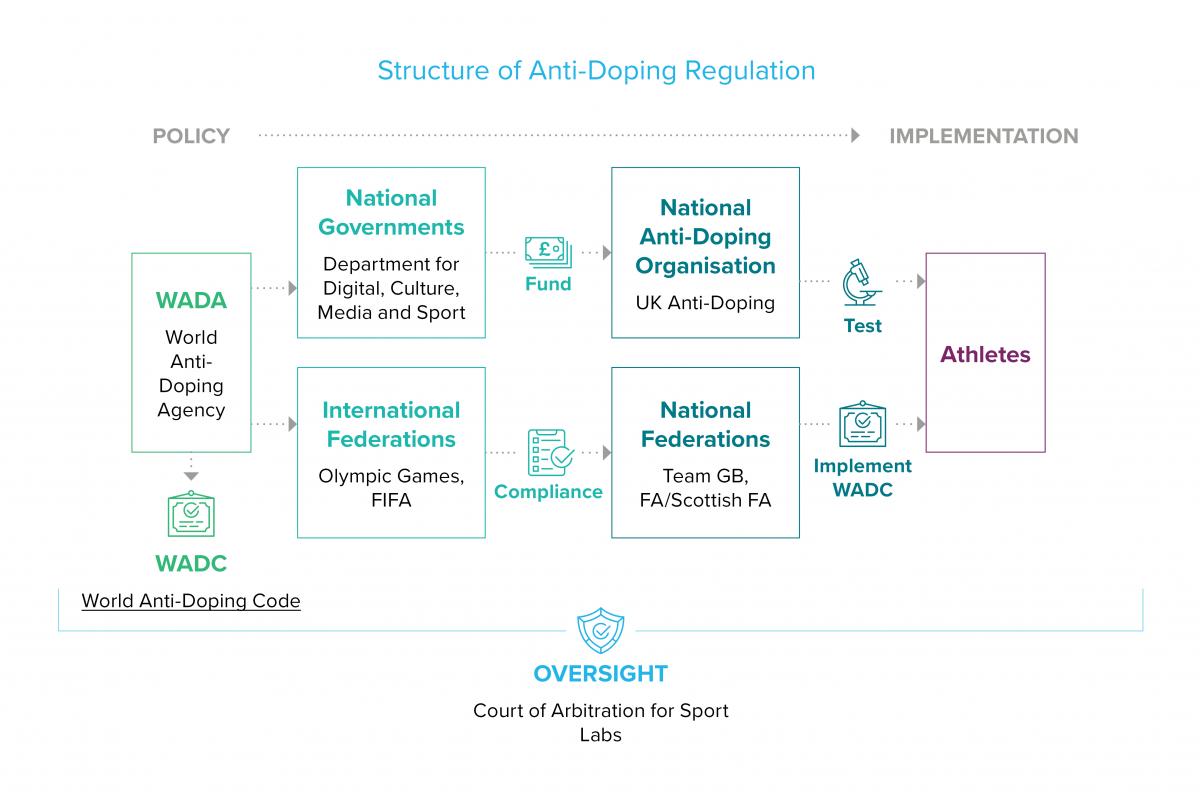

UK Anti-Doping (UKAD) is the organisation responsible for the implementation and management of anti-doping policy in the UK, and delivers testing, education and advice to competitive athletes within the UK. For an overview of the UK's anti-doping structure, please see our flowchart at the foot of this article.

Appeal/review process of a UK Anti-Doping violation

An athlete who has been charged by UKAD for a violation can either accept the conviction and any resulting ban (usually between two to four years) or they can dispute the allegations within a hearing. If an athlete contests the violation, the case will be referred to a National Anti-Doping Panel (NADP), where they will have the opportunity to reply to the charges and be legally represented. The NADP is a national tribunal and an appeal body for the UK which is entirely independent of sporting governing bodies and UKAD.

The panel consists of sport scientists, lawyers and medical professionals, and the cases are usually concluded within a matter of weeks. However, if the athlete or person suspected is participating in the Olympics, The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) will hear the matter independently. This review process is becoming increasingly of use to athletes, as doping scandals continue to be prevalent.

The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) also includes a right of appeal against any decision rendered under the World Anti-Doping Code (WADC). Article 13 of the WADC sets out the rules applicable for results management and appeals. The timing of any appeal is often of critical importance to an athlete. Under 13.2.2 of WADC, if the hearing is held by NADP it must be:

- a timely hearing;

- include a fair, impartial and independent hearing panel;

- the athlete is to have the right to be represented by Counsel; and

- a timely written reasoned decision is to be reached.

Further, under Article 13 of the WADC, those entitled to appeal include:

- the athlete or other person who is the subject of the decision being appealed;

- the other party to the case in which the decision was rendered;

- the relevant international federation;

- the national anti-doping organisation of the person’s country of residence or countries where the person is a national or license holder;

- the IOC or International Paralympic Committee, as applicable, where the decision may have an effect in relation to the Olympic Games or Paralympic Games, including decisions affecting eligibility for the Olympic Games or Paralympic Games; and

- WADA.

Any appeal must be filed within 21 days from the date of receipt of the decision. All parties to any CAS appeal must ensure that WADA and all other parties with a right to appeal have been given timely notice of the appeal.

What are the potential consequences of a doping offence?

WADA provides the list of sanctions which are issued in all sports and countries which fall under the WADC. The most common sanction is a ban from the sport. In some instances this can be for life. Other sanctions can include the removal of titles and medals from the athlete. If a doping offence is committed by a participant in a team sport this could have an effect on the whole team’s titles, particularly where more than one member of the team is found to have committed an offence.

The WADC also prescribes that all doping offences must be published, so there is likely to be a high level of scrutiny from others within sport and a record of any decision and the sanction imposed.

Could the doping ban be reduced?

There are prescribed bans, known as periods of ineligibility, which apply where a doping offence is committed. These bans can be reduced in certain circumstances, for example where:

- The offence is voluntarily admitted in the absence of other evidence.

- An agreement is reached with UKAD and WADA applying a reduction after assessing the individual’s degree of fault, the seriousness of the Anti-Doping Rule Violations and how quickly the violation was admitted.;

- The athlete established that the doping offence was not ‘intentional’ (as that term is defined in the rules) and prove how the substance entered their system.

- Establishing ‘No Fault or Negligence’, or alternatively ‘No Significant Fault or Negligence’. This can be established where the athlete individual can prove that they did not know or suspect, or could not have reasonably known or suspected, that they had violated an anti-doping rule. This is very rare and difficult to prove.

- Results Management Agreement - where an athlete faces a ban of four or more years, their ban can be reduced by one year if they accept they have committed an offence and the ramifications of this within 20 days.

- Substances of Abuse – an athlete could reduce their sanction by three months if they can prove their use of a Substance of Abuse was not in relation to a competition or sports performance.

For more information please contact Matt Phillip, Head of our Sports Law group, or your usual Shepherd and Wedderburn contact.

To find out more about how anti-doping regulation developed, please see our article Sports law: the history and development of anti-doping rules.