Contributors: Ruairidh Leishman

Date published: 17 February 2025

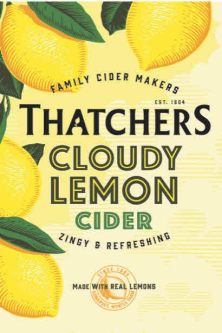

The cloudy world of “lookalike” products: Thatchers succeed in appeal against Aldi

Background

In 2024, the Intellectual Property Enterprise Court (IPEC) rejected Thatchers’ claim that Aldi had infringed their trade mark in respect of their cloudy lemon cider. The IPEC also rejected Thatchers’ claim under the law of passing off. Our analysis of that case can be found here. Thatchers has now succeeded in its appeal against the IPEC’s decision, with the Court of Appeal finding that the “resemblance cannot be coincidental” and that Aldi had infringed Thatchers’ trade mark.

Thatchers owns a trade mark for cider and alcoholic beverages, comprising of an illustration of lemons and including the words “THATCHERS CLOUDY LEMON CIDER” on a yellow background. Aldi subsequently launched a cloudy lemon cider under the sign “TAURUS CLOUDY CIDER LEMON”.

The productions of the respective ciders before both courts were as below:

Court of Appeal’s decision

The Court of Appeal agreed with Thatchers that the IPEC judge made several errors in her judgment. The Court of Appeal decided that it must reassess the elements where the judge made an error and found that Aldi had infringed Thatchers’ trade mark by taking unfair advantage of the mark.

Incorrect identification of the sign and similarity

The Court of Appeal said that the judge wrongly identified the sign used by Aldi as being the entire three-dimensional can of cider, including the text on the sides of the can. Rather, the sign is the graphic that is printed onto both the cardboard packaging and the face of the can. The text and additional information on the side of the can should not have been considered part of the sign for these proceedings.

This had a knock-on effect on the assessment of similarity. The Court of Appeal said that the IPEC judge should have assessed the similarity at a greater level than she had. The IPEC judge had erred in determining that because the trade mark was two-dimensional and the sign was three-dimensional, that was a point of difference between them.

Intention of Aldi

The Court of Appeal said that the IPEC judge had erred by failing to distinguish between an intention to deceive and an intention to take advantage of the trade mark’s reputation.

Upon taking into account the packaging, the Court of Appeal found that Aldi had significantly departed from its Taurus house style and had replicated the faint horizontal lines which are present in the Thatchers’ trade mark. These were both relevant to the assessment of intention to take advantage and the judge made an error in concluding otherwise.

Replicating the design, especially minor details which consumers may not notice (such as the faint horizontal lines), is evidence of intentionally close imitation of the trade mark. The Court of Appeal also noted that it was possible to convey a lemon-flavoured drink without such close imitation, as was demonstrated by the evidence put before the court of other lemon-flavoured drinks in the market.

The Court of Appeal reached the inescapable conclusion that Aldi intended for the sign to remind consumers of Thatchers’ trade mark. They naturally inferred that Aldi intended to take advantage of the trade mark to boost their sales.

Unfair advantage

The Court of Appeal noted that there was no discussion of Thatchers’ transfer of image argument by the IPEC judge, despite effectively rejecting this argument in deciding the case in favour of Aldi.

Thatchers argued that Aldi’s sign would cause a transfer of image from the Thatchers’ trade mark to the Aldi product in the mind of consumers, which is what was contemplated in the European Court of Justice’s definition of unfair advantage in L’Oréal SA v Bellure NV. Not considering this was an error of principle that required the Court of Appeal to assess this argument anew.

The Court of Appeal had already determined that Aldi intended to take advantage of Thatchers’ trade mark, which evidentially points towards a finding of unfair advantage (despite this not being clearly determined). The Court of Appeal also noted that Aldi had achieved significant sales in a short period of time and that there had been no evidence produced by Aldi that the product would have performed similarly without such a close imitation.

As such, the Court of Appeal agreed with Thatchers that this was a case of “a transfer of the image of the mark” and that Aldi were “riding on the coat-tails” of the trade mark, with Aldi being successful in their intention to benefit from the close imitation. This was an unfair advantage since Aldi profited from Thatchers’ investment into the promotion of the Thatchers cloudy lemon cider product and brand. Aldi did not compete purely on quality, price, or its own promotional campaigns.

Aldi therefore infringed Thatchers’ trade mark under Section 10(3).

Key takeaways

The two grounds of trade mark infringement under Section 10(2) and Section 10(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 share some common features, including the assessment of similarity. However, these are distinct and separate tests and should not be confused.

Own-brand products in supermarkets are unlikely to meet the Section 10(2) requirement of a likelihood of confusion as consumers are generally aware when a product is an own-brand as opposed to a branded product, especially when the name of the brand is prominently displayed, as it was for Thatchers and Taurus in this case. However, if the own-brand product is similar enough that it is found to take unfair advantage of a trade mark under Section 10(3), then this can infringe that trade mark regardless of whether the public would be confused as to the origin of the product.

Ultimately, this case should make it easier going forward for brands with a reputation and a trade mark to take action against “lookalike” products.

If you are interested in enforcing your intellectual property rights to protect your brand, or have any concerns about brand protection, please do not hesitate to contact our intellectual property team or our intellectual property disputes team for advice.

This article was co-authored by Trainee Jamie Hadden.

Contributors:

Ruairidh Leishman

Senior Associate

To find out more contact us here

Expertise: Corporate and Commercial, Dispute Resolution, Intellectual Property, Intellectual Property Disputes

Sectors: Drinks Sector, Retail and Consumer